Strengthening Liberal Democracies to Curb Populism

BSF 2020 Cas Mudde Populism in 2020

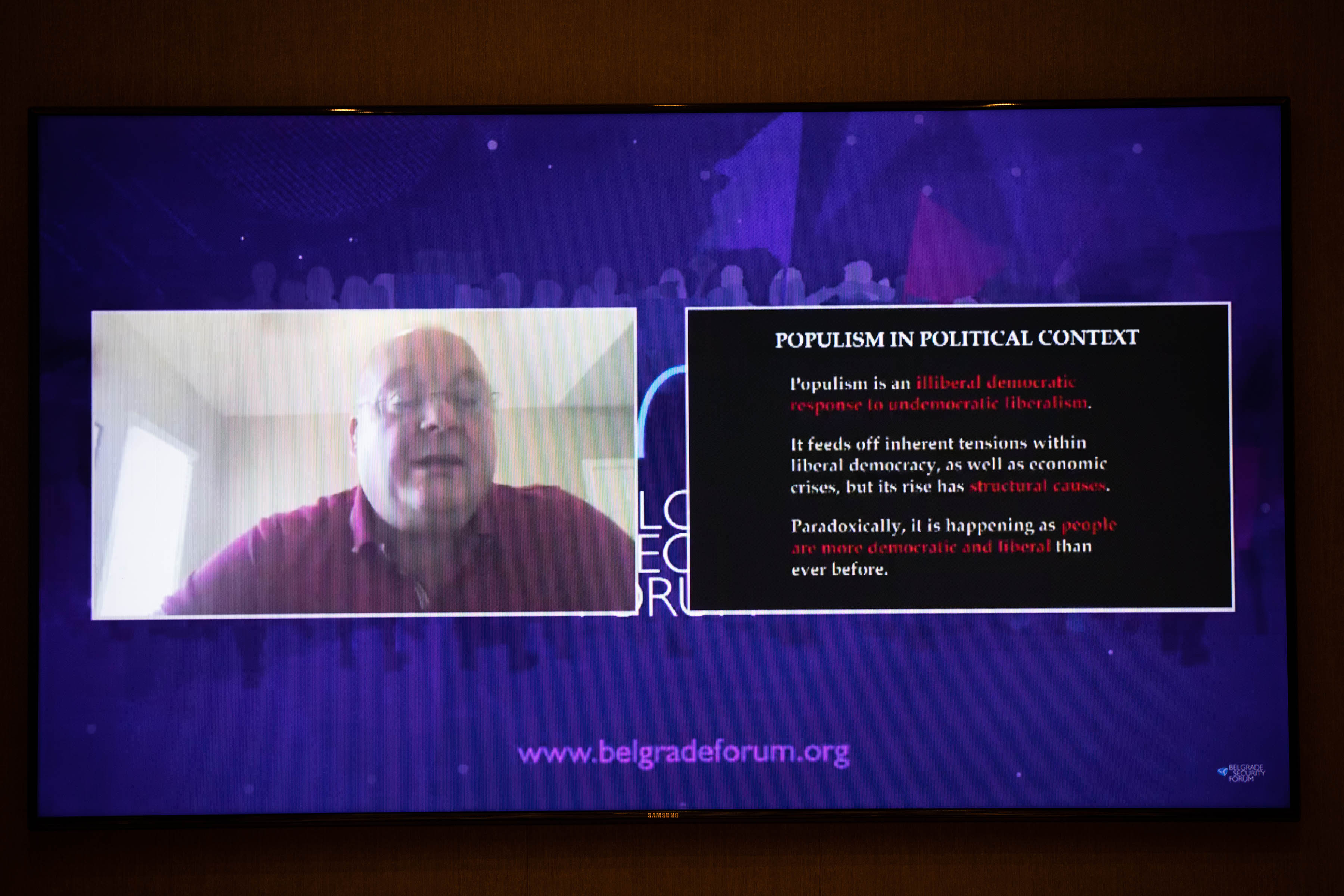

In the last decades, the world has seen an unprecedented rise in populist parties. In this session, Cas Mudde, Stanley Wade Shelton UGAF Professor (School of Public and International Affairs SPIA at the University of Georgia, USA), discussed the main features of populism, what makes it so unique, the effects of the upcoming US elections, and the way out of the era of Populist Zeitgeist.

Starting off his intervention, Mudde presented the viewers with his definition of populism, “as a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups: ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite'”, and argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.

Although it is very clear that the current trend of populism goes directly against mainstream values of democratic values, Mudde emphasised the importance of differentiating between left-wing and right-wing populism – decisive factor being the host ideology’.

Populism is pro-democracy but anti-liberal democracy. Populism actors can be left or right, depending on their host ideology. Syriza in Greece, for example, as a leftist party, combines populism with host ideology of socialism, while FPO in Austria, as a far-right party, combines populism with some form of nativism or xenophobic nationalism. Populism is almost always secondary to the host ideology – to understand the FPO, you need to understand its nativism.

Mudde explained that populism only tells a part of the story, but not the most important part of the story.

Populism is an illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism, he said touching upon the crucial issue of the discussion and, at the same time, the tools to combat the populist trend. It is an extreme form of the majoritarianism – majority should elect their leaders, but the majority can do whatever they want – even at the expense of liberal values and institutions.

While on the other hand, it responded to politics in which a lot of policies have become more liberal, but many of these were not really a part of democratic processes. He illustrated this by noting that many countries, the death penalty was abolished, but it was abolished outside of public debate, leaving minorities, and sometimes even majorities, in some countries that are pro-death penalty.

Depending on the outcome of the upcoming US elections, populism will lose its appeal and be pushed out of media narrative, or it will become normalised.

If Trump wins, populism could become normalised, while if Biden wins, and stand up, as he said, to populist leaders outside of the US, the potential change of media narrative that could follow, would enable the mainstream parties to reclaim the political agenda.

The way out of the Populist Zeitgeist is not by fighting the populism but by empowering the liberal democracy. Concluding the discussion, Mudde said it is more of a main symptom than the main problem of liberal democracies.

When liberal democracy functions well, populism is not successful. There is a lot of resentment towards liberal democracies, which needs to be addressed to marginalise populism. Therefore, the question is not how to fight populism, but how to strengthen liberal democracies.